Whispers and other sounds you were never meant to hear

Consider the much-discussed whisper that occurs at the end of Lost in Translation, Sofia Coppola’s critically acclaimed and prized 2003 film about two Americans who develop a friendship during lonely stays at a Tokyo hotel.

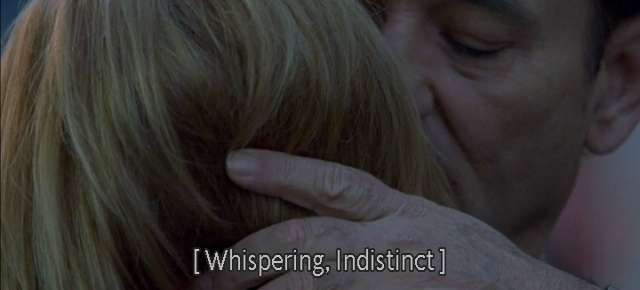

In the final scene, Bob [Bill Murray] whispers something to Charlotte [Scarlett Johansson]:

Source: Lost in Translation, 2003. DVD. Featured caption: [Whispering, Indistinct]

According to Roger Ebert, Bob and Charlotte “deserve their privacy”:

I loved the moment near the end when Bob runs after Charlotte and says something in her ear, and we’re not allowed to hear it.

We shouldn’t be allowed to hear it. It’s between them, and by this point in the movie, they’ve become real enough to deserve their privacy. Maybe he gave her his phone number. Or said he loved her. Or said she was a good person. Or thanked her. Or whispered, “Had we but world enough, and time…” and left her to look up the rest of it.

Through its exploration of alienation, loss, intimacy, and mystery, the film suggests in its gentle way that it might be better, really, if we didn’t know. The whisper was not meant for us, not meant to be captioned. Its mystery is encoded in a private language that the two participants, alone, can access and decode. Yet fans have continued to speculate. Perhaps that feeling of being lost in translation themselves is too much for some fans to bear. They yearn to unlock the mystery of that embrace — to be able to hear and know clearly — believing that the whispered message foretells the future of the relationship between the main characters, thus mediating the sought-after resolution.

Adding another layer of mystery is whether Coppola herself knew what Bob whispered into the ear of Charlotte. Peter Sciretta, of SlashFilm.com, reports that “Sofia Coppola gave interviews saying that nothing was officially scripted, and that only Johansson and Murray know what was really said.” Beyond Hollywood adds that “it was up to Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson.” Even the kiss was an “‘in the moment’ ad-lib between the performers,” according to IMDB. But IMDB also claims that Coppola did know the secret: “For years, no one other than Bill Murray, Scarlett Johannson and Sofia Coppola knew what Bob whispered to Charlotte in the final scene.”

Excavating the secret

What’s changed since then is not that someone has come forward (i.e. Coppola, Johannson, or Murray) but that a handful of resourceful fans have used “special sound equipment […] to make the conversation audible” (IMDB). Yet no attempt at sound editing has resolved the question of what was actually said, because no single edit has proven to be definitive (as evidenced by the ensuing debate in the comments sections of sound edited examples). Each attempt has in fact only added to the mystery by multiplying the possibilities and increasing the sense of anxiety for those viewers not content to give the characters their privacy, not content to dwell momentarily in that shared state of alienation and loss. Here’s one attempt to use sound editing to reveal the secret:

Here’s one popular attempt to excavate the meaning of the whisper by applying some audio filters to the clip:

The list of proposed whisper candidates includes:

- “When John [Charlotte’s husband] is waiting on the next business trip… go up to that man, and tell him the truth. Okay?” (YouTube video)

- “I love you. Don’t forget to always tell the truth. Okay?” (IMDB)

- “I have to be leaving, but I won’t let that come between us. Okay?”(Rotten Tomatoes, citing a YouTube video that has since been removed by YouTube. A number of other sites have also embedded this video, making it the most popular candidate.)

The author of the YouTube video above mentions three additional possibilities, presumably also the result of sound editing by others:

- “I love you, and everything you did. Go back there and tell him to try, OK?”

- “I’ll always remember the past few days with you. Don’t part mad… Tell him the truth. Okay?”

- “… on the flight back, tell him the truth. Okay?”

The candidates, interestingly, are pretty diverse, though a recurring theme is: Charlotte, tell your husband the truth (i.e. the truth, presumably, about her feelings for Bob). It’s hard to know exactly how many sound-edited clips have been produced. I found only two but the list of possibilities suggests there may more. There are also literally dozens of additional proposals, revisions, and corrections — some serious, some joking — in the comments sections of the sites where sound-edited examples are posted (e.g. see The Movie Blog’s comments section for examples of user-generated revisions/corrections/proposals).

We might turn, finally, in our quest to hear/know/translate the whisper, to the original movie shooting script. Unfortunately, the only version of the script available online is an earlier draft that makes no mention of a whisper, indistinct or otherwise. In the script, Bob says “Why are you crying?” Charlotte responds “I’ll miss you.” He “kisses her, hugs her good-bye” and then says, “I know, I’m going to miss you, too.”

The sound-edited examples show the lengths some hearing viewers will go to hear. The numerous user comments posted in response to the edited examples show the degree to which hearing viewers want to know, because knowing what Bob says is presumed to be key to unlocking what the the future holds for Charlotte and Bob. The examples provide an interesting case study for scholars and others interested in what Rosemarie Garland-Thomson (2006: 257) calls the “ability/disability system,” and in particular the ways in which any study of deafness is also, by necessity, a study of hearing and mainstream hearing culture. (While I assume that deaf and hard of hearing viewers share a desire to know what Bob says to Charlotte, the sound-edited videos, the embedded versions posted on other websites besides YouTube, and the user comments are all, as far as I can tell, produced by hearing users.)

Turning the tables on hearing viewers

The uncaptioned (or vaguely captioned) secret makes a compelling case for those interested in accessible media because it essentially turns the tables on hearing viewers, making them hard of hearing. The sound editing technologies are akin to poorly functioning hearing aids that tease the listener with the promise of full hearing (i.e. total knowledge and narrative resolution), but only frustrate, alienate, and confuse. The desire among hearing viewers to know what Bob whispers to Charlotte, and the resulting frustration and lack of clear resolution, is experienced by deaf and hard of hearing viewers (indeed, anyone who relies on closed captions) every time closed captions are not available. That feeling of alienation — of being lost in translation — is a regular occurrence for caption users who must contend with online environments that are, with few exceptions, inaccessible.

Reference

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie (2006 [2002]). “Integrating disability, transforming feminist theory.” In L. Davis (Ed.) The Disability Studies Reader (257-273). 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

[Fair use notice: The videos on this site are transformative works used in good faith, in keeping with Section 107 of U.S. copyright law, and as such constitute fair use of copyrighted material. Read this site’s full fair use notice.]