Captioned puns and wordplay

In the case of captioned wordplay, the difference between writing and speaking, text and sound, is obvious. What works in speech doesn’t work — or works differently — on the caption layer.

I’ve explored this issue in at least one previous post.

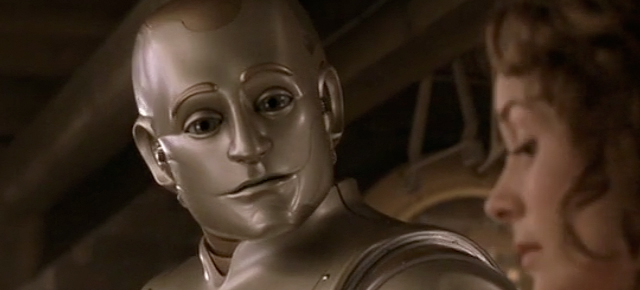

A hearing audience watching the following scene from Bicentennial Man (1999) with the captions turned off will most likely experience a disconnect between sound and meaning. What one character (the android) really means is not what he is initially interpreted to be saying by both the other character in the scene (“Little Miss”) and the listening audience. If you are a hearing viewer and have not seen the movie, I don’t want to give it away. First, without captions:

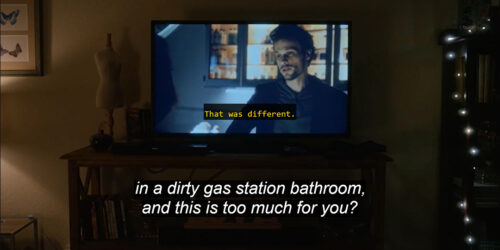

Viewer and “Little Miss” are joined together in the shared dissonance they experience when the android fails to stay on topic. Now watch it again with the official DVD closed captions:

The real meaning of “board” is never a mystery to caption viewers. Whereas the uncaptioned version is intended to draw hearing viewers into making the wrong assumption about what the android is saying, the captioned version prevents viewers from assuming that the android is asking if Little Miss is “bored.” The uncaptioned version connects the viewer to Little Miss (both make the same assumption); the captioned version separates them (since the caption viewer does not, as Little Miss does, misinterpret what the android is asking).

[Fair use notice: The videos on this site are transformative works used in good faith, in keeping with Section 107 of U.S. copyright law, and as such constitute fair use of copyrighted material. Read this site’s full fair use notice.]