Captioning 101: When music lyrics trigger an explosion, you just might want to caption them.

When music lyrics are instrumental to a film’s plot, they need to be captioned. It’s as simple as that. If captioners are responsible for captioning all significant sounds, then any sound that’s instrumental to the plot needs to be captioned.

Easier said than done, it seems.

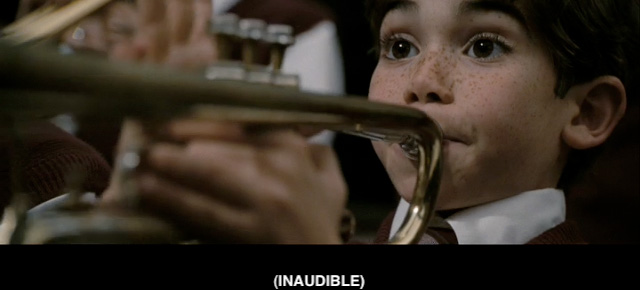

Consider the DVD release of Eagle Eye, a 2008 action flick starring Shia LaBeouf and Michelle Monaghan. At the end of the movie [Spoiler Alert!], a bomb is triggered to explode inside the U.S. Capitol when a school band hits the high note at the end of the U.S. national anthem. It’s a bit more involved than that, but that will do. (See Wikipedia for the movie details.)

In other words, the entire movie comes down to a song, the lyrics that accompany it, and a high note corresponding to the word “free” in the anthem. When the band hits that high F, boom!

If ever there was a case to be made for the significance of music lyrics in a movie, this is it.

But the lyrics are only partially captioned. While an on-screen graphic lets us know that the dreaded note is coming soon, the graphic isn’t supplemented with fully captioned music lyrics. In this case, the significance of the lyrics trumps how loud or quiet they are. Indeed, significance should always trump sound volume. If it’s significant, it needs to be captioned.

Instead of “(SINGING CONTINUES),” the caption should have read, “…the bombs bursting in air, / Gave proof through the night.” The word “night” is barely audible; the remainder of that line (“that our flag was still there”) can’t be heard, and we see Monaghan running after her son, the little trumpet player who will play the fated note.

But just because hearing viewers can’t clearly hear every word in the song doesn’t mean the lyrics don’t need to be captioned. Why? For at least two reasons: 1) The song is playing almost in real time for an audience who knows those lyrics and melody by heart (in the U.S. at least). Even though the words can’t be heard, the melody continues. If hearing viewers can continue to follow the melody in the absence of words, caption readers should be able to do so too. The best way to do this is by captioning the words that correspond to the popular melody. 2) The scene builds suspense through the melody and lyrics of a well-known song. If the audience can’t follow the melody and anticipate the note at the end of the song, then the scene can’t build the suspense required to be effective.

Of course, these reasons are complicated by the dramatic quiet that falls on the place when Monaghan runs down the aisle. Still, the trumpet can be heard playing the melody, which is a cue to listeners that the dreaded musical note approaches. The lyrics quickly return with the final two lines of the song (“O! say does that star-spangled banner…”). These two lines, right up to “free” or “fr–,” must be captioned, even if every word can’t be heard loud and clear. The hearing audience is following a well-known melody. The caption-reading audience must be able to follow along as easily. When a song lyric (or musical note, to be precise) triggers a movie-ending explosion, it needs to be captioned.

Captioning Music: What the style guides say

Two well-known style guides offer the following guidelines for captioning music.

According to WGBH,

- “[U]se the musical note…to differentiate song from spoken word” (♪);

- Caption “Songs and jingles…verbatim”;

- Describe instrumental music, especially “the title of a song whenever possible.”

- “[U]se descriptions that indicate the mood” of the music;

- “If music contains lyrics, caption the lyrics verbatim.” Introduce the lyrics “with the name of the vocalist/vocal group, the title (in brackets) if known/significant, and if the presentation rate permits”;

- “Caption lyrics with music icons (♪)”;

- Use a description, including performer and title, for instrumental or background music or “when verbatim captioning would exceed the presentation rate.”

- Use the musical note by itself “in the upper right corner of the screen” “[f]or background music that is not important to the content of the program”;

[Fair use notice: The videos on this site are transformative works used in good faith, in keeping with Section 107 of U.S. copyright law, and as such constitute fair use of copyrighted material. Read this site’s full fair use notice.]